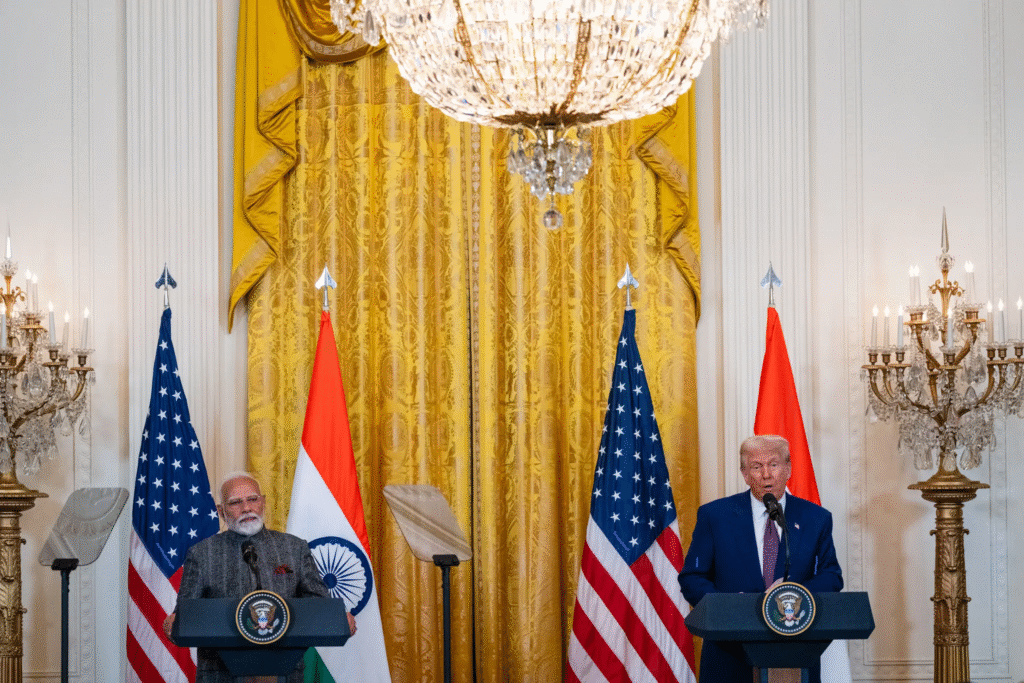

The Trade That Ties the Indian and American Economies Together

Trump prioritizes the trade in manufactured goods, in which Indian exports more to the United States than it imports. However, the two nations have a balanced trade in services.

In the last month, the economic connection between India and the United States has been put in serious danger of breaking. Beginning next week, President Trump is prepared to slap a 50% tariff on Indian products. In turn, those tariffs pose a threat to destroy firms that rely on the export of Indian electronics, jewelry, seafood, carpets, and other commodities.

The contribution of services to the overall trade between the United States and India, which surpassed $200 billion last year, is unfortunately ignored in the chaos.

The $46 billion trade gap between the United States and Indian enterprises in 2024 has been a major area of attention for Mr. Trump. In contrast, Indian and American businesses exchanged about $84 billion worth of services during the same period. For the past few years, the two nations have maintained a close equilibrium in the exchange of services.

One major factor is that the majority of Fortune 500 businesses, including Walmart, Lowe’s, Microsoft, and Meta, currently have offshore operations throughout India.

Multinational corporations headquartered in the United States are constructing permanent corporate offices in India’s largest cities in order to perform operations globally. Their yearly payroll is much higher than the U.S. trade deficit that worries Mr. Trump. The United States is home to many companies with strong ties to India, and that is the money that supports India’s economy.

The majority of Goldman Sachs employees are located in the southern cities of Bangalore and Hyderabad, where they had been taking care of global operations. In Mumbai, India’s financial hub, the company has less staff. Additionally, it revealed a Mumbai expansion on Monday, including a new office that is 50% bigger than its current site. The local stock markets, currently the fourth most valuable in the globe, are where those bankers operate.

Since traded services are, by definition, less tangible than traded goods. During Mr. Trump’s first term, tariffs on pecans, bourbon, and Harley-Davidsons were discussed back and forth by his staff and Indian negotiators.

However, American bottom lines depend just as much on services. The value of the services the United States sells globally exceeds the value of its purchases. Key categories include finance, education, transportation, and consulting. In India, American businesses in each of those sectors make a lot of money.

The United States receives the most international students from India. Each dollar they pay for tuition is considered a service export from the United States to India. In addition to their medical costs in the United States, their plane fare is also covered (unless they traveled on Air India).

The goods traded between the two nations are strangely compatible.

Amitendu Palit the erstwhile Indian trade official and now research fellow at the National University of Singapore, stated that In India, we have this unique model. The nation’s workforce is unrivaled in its ability to manage all types of business operations, from entry-level to executive, in the service sector.

According to Mr. Palit, the worth of the services offered by American companies’ Indian-based offices contributes to the profit of those parent companies. “That’s basically what’s pushing the bilateral services trade,” he said.

In contrast to trade in goods, the two nations’ trade in services has increased by double digits in recent years and has also gotten more complex. Indian companies often provided telemarketing and customer service to American customers 20 years ago. Currently, Indian employees who are directly employed by American subsidiaries are conducting cutting-edge research in research labs, engineering oil fields, and developing legal strategies.

In comparison to the rest of Asia, services are particularly vital to the economies of the United States and India. For Japan and South Korea, as well as for China, which had a trade surplus of $1 trillion with the rest of the globe last year, exports are the cornerstone of economic activity. India’s neighbors Bangladesh and Sri Lanka share the same situation, as does the majority of Southeast Asia.

India has attempted to close the gap with them. Since 2015, its factory-centric development initiatives have been known by the slogan “Make in India.” The main attraction is that, of the sort that India’s young population so needs, factory work tends to generating employment.

In the last ten years, however, employment in services has surpassed the manufacturing sector of the national economy, which has really decreased. The offshore office parks of foreign corporations, which are projected to employ at least 2.5 million Indians nationwide by 2030, the vast majority of whom will earn salaries that place them in the upper middle class, are cited by economists as evidence of their success.

Consequently, India’s Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s standoff with Mr. Trump has significant repercussions for India. A 50% duty on Indian products for American importers may harm the livelihoods of workers throughout India.

Mr. Trump has not made any public threats about attempting to prevent American firms from opening operations in India. However, two industry officials who requested anonymity in order to speak freely about their worries stated that the strain between the two governments might put at risk the billions of dollars that firms have invested in their operations in India.