For 24 years, Pulp remained silent. This Is What Caused Jarvis Cocker and Company to Return.

Pulp and The frontman recalled, “Someone said, oh, that’s very age appropriate,” after listening to the band’s new album. “I took it as a compliment.”

Jarvis Cocker has the right to express his opinions. The well-liked Britpop band Pulp’s mop-topped, bespectacled frontman is popular for his witty turns of speech and biting allusions, which also bring his lyrics to life.

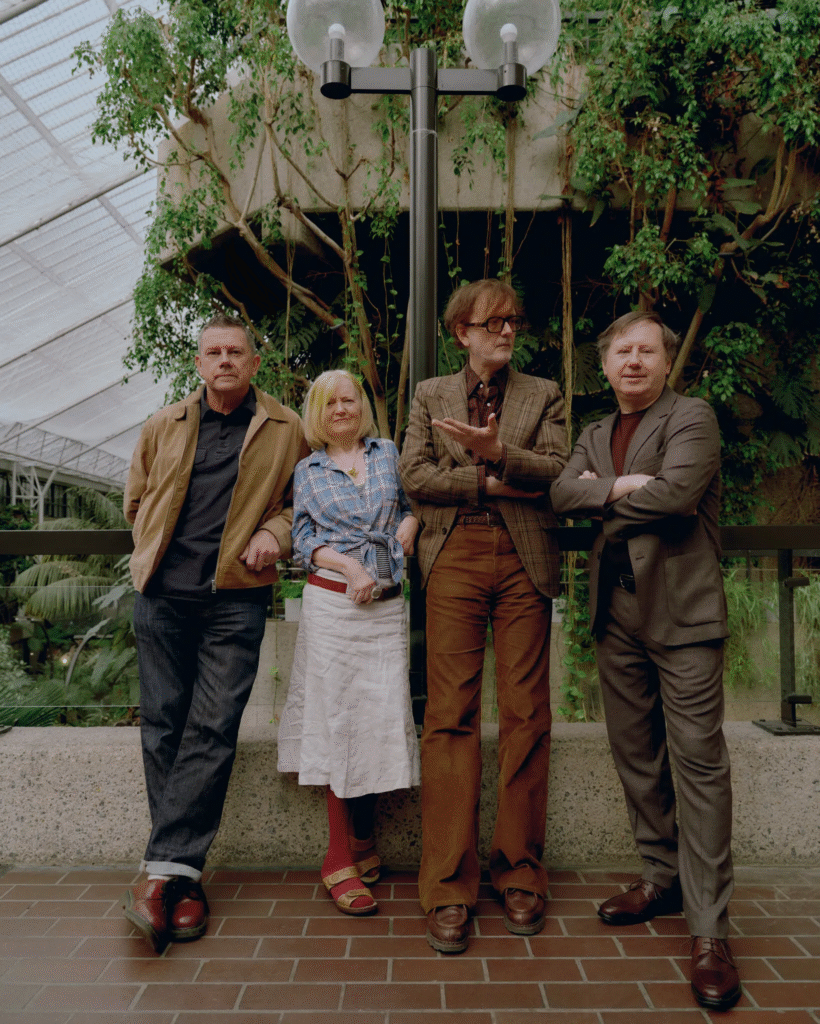

Bring him into a space with his bandmates — he and the three longest-tenured members had met last month at the Barbican Center in central London to discuss their latest album — and he will be happy to talk about the underlying themes of pop music (“repressed feelings”) and the unexpected challenges of being in a band: “You can’t get insurance! It’s loads more expensive for a musician.”

Streaming poses another hazard. “We’re in a situation now where you could live your entire life without ever listening to a piece of music more than once; you can just let it all just go past you, in a kind of scented candle vibe,” he said with horror.

As its name implies, Pulp is more visceral than that, with humorously observed dance-floor anthems that investigate the social pecking order, such as the timeless 1995 song “Common People.” Recently, Cocker said he came to the conclusion that what “made Pulp songs interesting” is that “they’re often quite frenetic, trying to get some idea across or to work something out in your mind. Occasionally, nearly hysterical.

At least that’s what carried them through their 1990s peak. However, “More,” Pulp’s first album in almost twenty-five years, which was released on June 6, takes a different tack: it’s more reflective and has more space to breathe. “Someone said, oh, that’s very age appropriate,” Cocker, 61, said when he played it in the offices of Pulp’s label, Rough Trade. “I took it as a compliment.”

His bandmates—keyboardist Candida Doyle, guitarist Mark Webber, and drummer Nick Banks—sat around a lengthy conference table at the Barbican, the cultural hub where they had performed over the years, and were generally in agreement with their songwriter and somewhat democratic leader. However, they occasionally giggled at him with affection.

As in the time during the band’s early 2000s hiatus when he described his fateful choice to relocate to Paris and what he took to be a signal from the cosmos that he should stop playing music.

He had tied his most valuable and prized instrument, an acoustic Gibson, to the top of his vehicle. “It fell off as we were driving,” he remembered. “Got run over by a lorry. Completely destroyed.” His bandmates burst out laughing. “It was the first time I’d ever attempted to put anything on a roof rack,” he continued, and they lost it. (“It’s so typical!” Webber spluttered.) Cocker responded with mock indignation: “What are you laughing at?! You should be crying about that!”

However, Pulp is free to make fun of you after playing together for three decades. Banks, 59, described them as having “mellowed” and become “more accepting of each other.” Doyle, 61, used the word “harmonious” to describe the album-making process, which involved them assigning a numerical rating to each demo in order to decide what would make the cut. (The highest score went to a gloomy, atmospheric track now called “My Sex.”) At this point, the stakes are different, and they may or may not experience a resurgence in popularity. “There isn’t really a lot of pressure for me,” Webber, 54, stated.

In a sector that is constantly changing, Cocker questioned, what were the success metrics? “Candida?”

She responded, “Whether I enjoy it or not,” at which point the men burst out laughing.

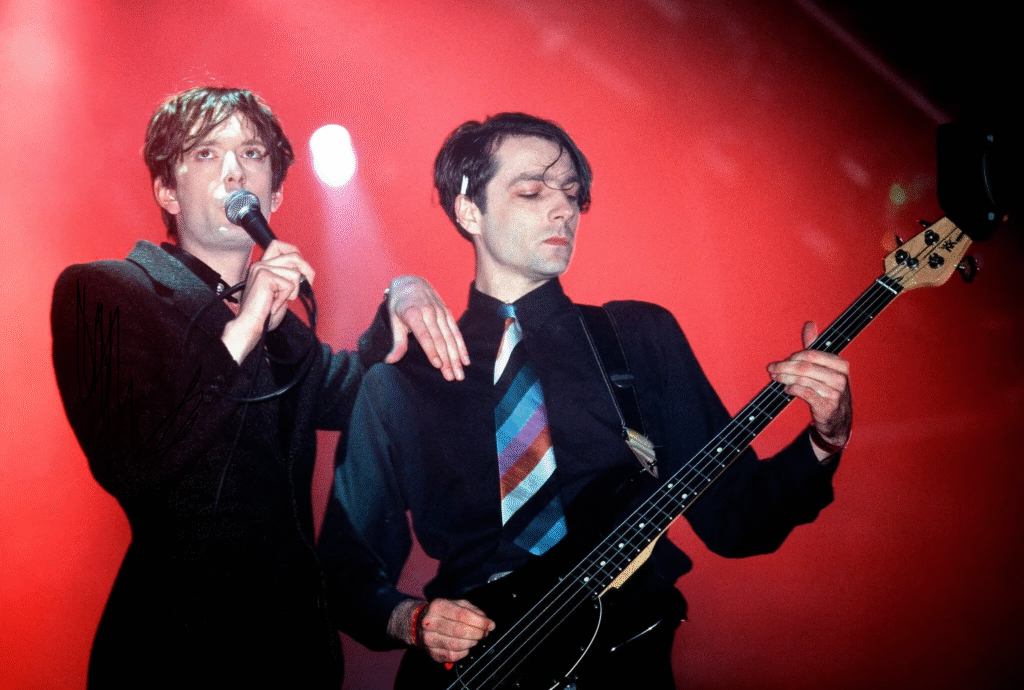

With a singular focus on the aspirational career of a pop star, Cocker founded the band in his working-class hometown of Sheffield, England, in 1978, when he was a teenager. The band struggled for ten years in obscurity in Sheffield, with a changing lineup and D.I.Y. scrabbling. Following Cocker’s time at art college in London, Pulp rose to prominence, especially in the UK, where it was a member of the Britpop trifecta alongside Oasis and Blur—the most amusing aspect, on purpose.

The magic of Pulp, according to James Murphy, the frontman of LCD Soundsystem and a buddy of Cocker’s, is that the songs are serious yet not too serious. In a telephone interview, Murphy stated that there is “an infinite possibility of depth and humor and wit and earnestness and flippancy,” adding, “I don’t think that those things are in conflict when they’re done well.”

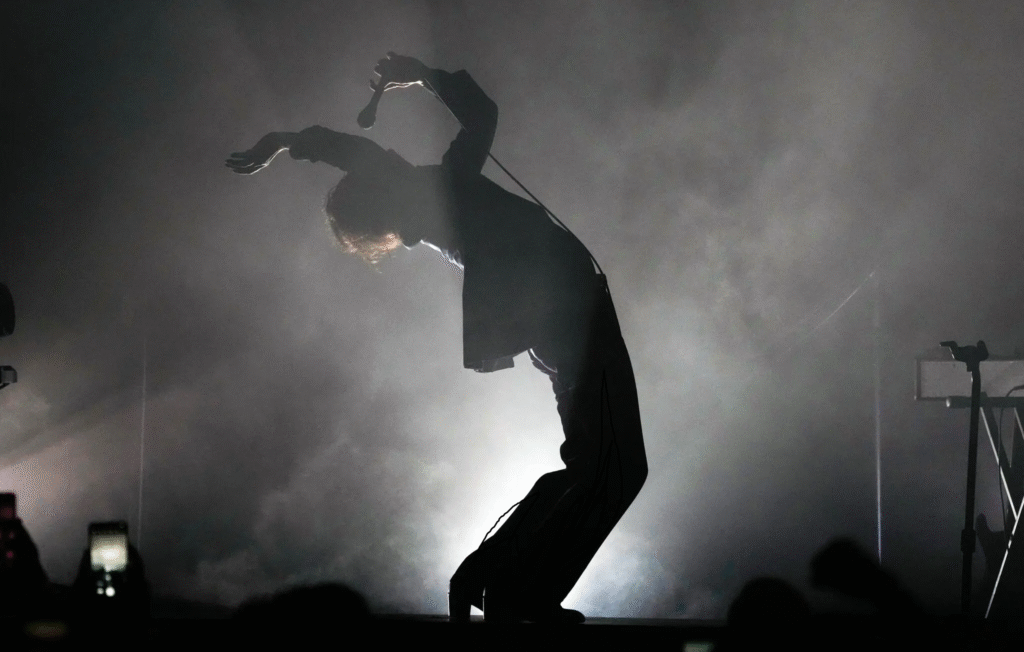

Banks’s aggressive drumming and Cocker’s impulsive struts and turns in live performances helped the band gain popularity; their rise was a representation of relatable effort. When Pulp headlined the Glastonbury Festival in 1995, Cocker addressed the audience, saying, “If a lanky geck like me can do it, you can do it too,” using a British word for geek.

However, by 2002, Pulp had become a supernova: its star had fallen under its own weight. “There wasn’t a falling out,” Webber stated. “Just ran out of steam,” the banks concurred. They nonetheless stated that there was no hope of Pulp’s rebirth.

After that came real lives and different professions. Webber was a writer and indie film curator; Banks ran his family pottery company in Sheffield; and Doyle, who had rheumatoid arthritis as a teenager, trained as a counselor and became an advocate. They all benefited financially from their success in the 1990s. In addition to working as an editor at large for the publisher Faber and Faber and as a BBC reporter, Cocker also had a side project called Jarv Is… (In order to reduce my premium for insurance reasons, I listed the broadcasting position.)

The next step was a couple of well-received reunion trips. The first, in 2011, was intended, according to Cocker, “to try and finish things off in a nicer way” (including with the guitarist Russell Senior, who had previously left the band). Additionally, Cocker sought to overcome the youthful notion that fame would fix all of his issues.

“No, it didn’t,” he stated. “One of the things that motivates me to do it now is to attempt to do it right this time.” (He left open the possibility that this might be impossible.)

Pulp’s eighth studio album, “More,” is dedicated to Steve Mackey, their bassist who passed away in 2023. Now featuring a string section and choir, it tempers what Doyle referred to as the “tense energy” of their previous work for Cocker’s midlife reflections and talky meditations, which were inspired by new numbers that Cocker auditioned during soundchecks.

In the album notes, Cocker said, “I’ve always had a bit of an obsession with age.” (He wrote the arcing ballad “Help the Aged” at the age of 33.) “I’ve never truly desired to grow up, so it’s a significant accomplishment to say that I am now. In the warning track “Grown Ups,” he states: “Life’s too short to drink bad wine.” And that’s scary.”

Cocker, who was formerly a British heartthrob wearing mod clothing and stack-heeled boots, is still a dandy, but now he sports plaid and thin corduroy with perpetually disheveled hair; in his all-brown tones, he almost blended into the 1970s russets of the Barbican. “I once read this thing that said, if you want to do something original, then try and copy something exactly,” he said as he exited the building to hold a lecture with a sculptor at a 19th-century chapel.

Cocker is a kind of cultural double agent: he is a gentle aesthete in everyday life but a huge sensation on the stage. “I was dumbfounded,” Murphy said of the first time he saw him play (on the 2012 Coachella cruise), which included skyward fingers and lengthy knee bends. “He’s so magnetic. Continually tossing shapes, with a lanky frame. If you sketched a cartoon of that, it would be more realistic because it seems almost impossible as a human being. It’s an overstatement of presence.

Cocker, for his part, stated that he has no plans and has few memories of performances. “That’s why I like music,” he said, adding that it “bypasses your intellect.”

For Pulp, it was an unheard-of shortness; their previous album, “We Love Life,” which was released in 2001, took nearly a year to produce, and “This Is Hardcore,” which was released in 1998, took even longer, a process the band had no desire to go through again. “More” was finished in three weeks by the group.

In order to replicate the atmosphere of a live concert, they recorded everyone in the same room, along with James Ford (Arctic Monkeys, Depeche Mode), the producer, who also plugged his mixing console in there. Ford stated in an interview that he prefers to work quickly and “capture more of a kind of photographic moment.” He added, “My preference is always for the feel and the vibe of it, over the precision of the sonics.”

Murphy told me he adores that the group’s music is “a little [expletive] wonky.”

“They have never been rounded out and made to sound like everything else,” he said. Murphy stated that the two performers will be performing at the Hollywood Bowl this fall in a pairing that he had been attempting to set up “for a very, very long time.”

Both Ford and he raved about Cocker’s words. Ford stated, “They’re so kind of matter-of-fact, but then cosmic at the same time.” (Faber made an effort to emphasize that a compilation of Cocker’s lyrics, titled “Mother, Brother, Lover,” which he published in 2011, was by no means poetry.)

“More” also marked a shift in his writing style. He preceded all of the other albums with melody and mumbled noises until he eventually uttered a few words, sometimes at the very last moment. In this case, he arrived at the studio prepared with his language. “I was born / To perform,” he declares on the synthy, nostalgia-fueled opening song, “Spike Island,” adding, “It’s a calling / I exist / To do this / Shouting and pointing.” “Maturity!”

Is he being sarcastic? Like much of Pulp, it is layered. The name is taken from a 1990 performance by the well-loved Manchester band the Stone Roses, which was a notoriously disorganized occasion that tens of thousands of people attended and which helped give rise to the Britpop movement.

With the seemingly endless rivalry between Oasis and Pulp’s members now returning to the road, it’s seeing a little bit of a comeback. The band members were divided about whether they should attend the stadium events, but Cocker was intrigued since Pulp was supporting Blur on a U.S. tour in the 1990s when he first met them. One of the Oasis concerts took place on a night when I wasn’t working in San Francisco.

“We asked if we could go see it,” he remembered, “and they said yes, ‘as long as Jarvis comes onto the tour bus and talks to us before.'” He parked. “I was led in on my own and set down at one of those little tables and spoke to them for a bit.” “I thought that was quite an interesting thing, bit of a mind game, just to say if you want to come and see us you have to interact,” he says, though he can’t remember the subject matter. I lived. (Now, all he wants is a place on the guest list, and he’s attempting to control his expectations.)

No matter how hard he tries, Cocker is unable to let go of his musical career. In a way, it’s simple since you’ll always return to it,” he remarked, adding that he was writing songs again a month after his guitar was wrecked on the way to Paris. There’s no need for discussion or deliberation. It may make you a little insane. However, many people simply stroll about without having a clear idea of what they should be doing. It’s wonderful to always have something sort of floating above you.

“I think so,” he stated softly.

Banks said, “That’s beautiful,” and the ensemble murmured in agreement.