After stepping away from the stage, Gilberto Gil declared, “My music will continue.”

The acclaimed Brazilian singer and composer, whose career in music and politics has lasted for six decades, is now 83 years old and on a farewell trip.

Bob Dylan performed onstage for the first time a month after Gilberto Gil began his exile.

At the time, in August 1969, Gil was only 27 years old, and he has since become a well-known worldwide personality with a 60-year career behind him. He had been “invited” to leave Brazil by the military dictatorship following, among other things, an arrest on suspicion of “inciting youth to rebel” during a performance in Rio de Janeiro. Compelled to run, Gil chose London as his new home since it was a center for foreign musicians and artists, and it offered a lively cultural environment and creative license.

He knew he couldn’t pass up the opportunity to see Dylan perform his first gig since a motorcycle accident nearly killed him, and he arrived just in time for the Isle of Wight Festival.

In a recent interview, Gil stated, “It’s almost that passivity. He has the calmness on stage without many exuberant gestures. I wanted to absorb that and use it in my own performance.”

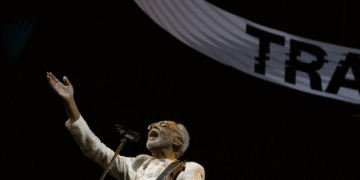

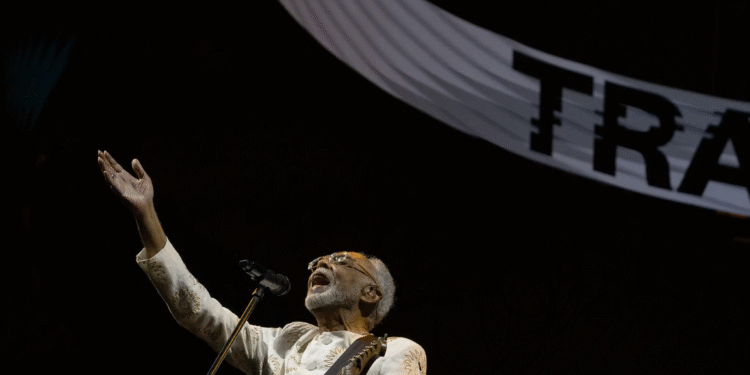

And throughout the years, regardless of whether his image was that of a wise thinker or a motivator of young people, he did. The eloquence of his words and the memories his music brought up were what mesmerized 40,000 people in São Paulo this April, even as Gil was performing there during his farewell tour.

As Gil led the audience through the various genres of his career, including samba, baião, jazz, reggae, rock, and international pop, he was backed by a chorus of voices. Gil is an innovator who has a talent for maintaining his country’s traditional forms while expanding upon them. He has employed both his music and his voice to instill in his fellow Brazilians a sense of pride in their origins and optimism for the future. He served as Brazil’s Minister of Culture from 2003 to 2008 and has been involved in politics since 1987, in addition to publishing a number of albums.

At 83, Gil acknowledges that it’s time for him to take things easy. He isn’t afraid to discuss getting older; it’s simply another step in his life’s transformation. Furthermore, the title of his last stadium tour was — The title of his 1984 song, which addresses the passage of time, the shortness of life, and the need for change, is called Time Is King.

“The categories of ‘last tour,’ ‘last chapter,’ and ‘end of career’ are all valid,” he stated. “Basically, I’m on a journey that will bring a cycle of over 60 years to a close.”

However, Gil maintained that the choice to give up live performances is not a retreat from music. It’s a method of rediscovering it.

“I’ll always have my guitar, my inseparable companion,” he stated in a recent video interview from Rio, where he was taking a break between performances to spend time with his family. “However, I will have a more open and open connection with it. When you have fewer commitments, things are simpler. I will eventually have a lot more time to return to writing and maybe even producing albums. My music will go on.

The start of Gil’s musical career was in the Brazilian city of Salvador, in the northeast of the country. There, as a child, he first heard the South African civil rights activist and singer-songwriter Miriam Makeba on records at a friend’s house. It ignited his curiosity about how African music brought some of his favorite Brazilian sounds to life, and established a connection between music and politics at an early age.

Gil learned his first instrument, accordion, at the age of 17, joined a band called Os Desafinados (the Out-of-Tunes) and turned his attention to bossa nova, a delicate new style emerging from Rio de Janeiro with syncopated melodies and jazz-influenced harmonies, inspired by Luiz Gonzaga, the Afro-Brazilian musician known as the King of Baião.

“I believe that I belong to a group of artists who were heavily influenced by the very nature of how Brazilian music itself came to be,” Gil stated “I was born to this swarm pot of musicality.”

One of the most important partnerships of his career would be the one he formed with Caetano Veloso, with whom he struck up a close friendship after being introduced to him by producer Roberto Santana in 1963. Together with Maria Bethânia, Gal Costa, Tom Zé, and the members of the group Os Mutantes, Veloso’s sister led Tropicália, a cultural movement that questioned the political and social norms of their nation by fusing Brazilian styles from their youth with outside influences such as pop psychedelic rock. David Byrne was one of the musicians who drew inspiration from the ideas of unrestricted individual liberty expressed in the music.

“The thing that drew me to it was the sophistication — the musical sophistication but also the sophistication they had about their situation globally,” the Talking Heads frontman said in 1999. “What constituted ‘center,’ and what constituted ‘periphery’?”

Gil and Veloso’s defiant humor was not appreciated by the military regime, so they were in London for three years, which he now remembers as a mixed experience.

I just rebuilt my life with Sandra, he said, referring to his second wife, and had son, the first of our three children, in London, he said. It was the domestic life that was very simple at the same time there was the presence of Brazilian artist from all areas: music theater and film. Additionally, there was this fresh atmosphere with English artists who were also eager to work with us. It was all of that, plus the desire for Brazil. The distance was so great.

“However,” he said, “I am extremely grateful for what London did for me during the dictatorship.”

There, in 1971, Gil published his well-received self-titled record. He enhanced his understanding of jazz and reggae by performing at the Glastonbury Festival and at concert halls throughout Europe.

His music underwent an omnivorous change when he returned to Brazil, incorporating elements of rock, reggae, and African music while exploring the wealth of native Brazilian genres.

“I believe I heard Gilberto Gil before I even realized it was Gilberto Gil,” said Iza, the 34-year-old Brazilian pop singer who is famous for her pop music with Afrobeats and R&B influences. “He is a product of my family’s imagination, the source of my musical identity. He demonstrated to me that Brazilian, Black, music is respectable. He helps us feel like we’re a part of something and can love our roots.

However, Gil aimed to introduce the world to more than simply music. When the family resided in Ituaçu, a little rural village in the northeastern state of Bahia, he had seen his father, who was a doctor by trade, try his hand at local politics as a kid.

“I lived in that world with citizens, candidates, and voters for a while when I was a kid,” he said. “And in a way it left its mark on my soul and in my conscience.”

Mikhail Gorbachev’s perestroika and glasnost reforms had little bearing on Gil’s choice to join politics in the late 1980s. That was when I understood that political life required impulses, enthusiasm, analyses, he said.

In 1988, his aspirations to run for mayor of Salvador were destroyed by criticism from his more conservative party colleagues, who were uneasy with his sense of style—he favored tunics over suits and wore earrings and an Afro—as well as with some of his policies, such as protecting the environment and Afro-Brazilian culture. He chose to run for, and win, a seat on the city council.

He founded initiatives to increase Brazil’s cultural, artistic, and ethnic variety after eventually becoming the country’s minister of culture. It was a gratifying period, he said, but it required some sacrifice.

“For at least ten years, I had to split my time between music and politics,” he stated, “and music suffered. It was likely the hardest moment in my musical career.”

He’s in the mood to relax a little now. “I already feel older, more tired, and in need of a less intense pace,” he stated.

Gil stated that the reaction to his last tour, which is the first time he has performed so many large concerts consecutively—some with crowds of over 60,000—has been “surprisingly enthusiastic,above my own expectations.” With the help of his sons Bem and José Gil, both of whom play in his band and serve as the tour’s musical directors, he developed set lists that were organized by genre. He chose three to five songs in each genre that he knew audiences would want to hear one last time, some with new instrumentation and others, like “Procissão,” returning to the original arrangements.

For the first time, he’s also performed live “Cálice,” a song full of allusions to freedom that he coauthored with Chico Buarque in 1973 during the military dictatorship but was unable to publish due to censorship until 1978.

According to him, the tour has given him joy, but it will also give him saudade, which is a Portuguese term that is hard to translate but which includes a feeling of longing, desire, or nostalgia.

It’s a mixed feeling,he said. Although there novelty and surprises in what I’m doing, it’s an experience I won’t continue to have.

For instance, Gil made sure to perform all the crowd-pleasers during the April event in São Paulo, including “Aquele Abraço” and “Andar com Fé,” which were essential, and he also included songs that reflected significant moments in his own life, such as “Domingo no Parque,” which has been a staple of Brazilian culture ever since Gil performed it with Os Mutantes on television in 1967.

Gil stood behind the microphone with a guitar in hand and a smile as images of his life flashed across the enormous screens behind him, including intimate photos of his family, historical photographs of Afro-Brazilian culture, and portraits of his greatest inspirations.