Trump’s Trade Policies Sort Manufacturers Into Winners and Losers

Tariffs have protected some companies, but more often they’ve hit the parts and materials many factories need to make finished goods.

For a long time, President Trump has stated that tariffs would bring about a revival in manufacturing. As factory employment continued to sink in recent months, he assured Americans it would just take a little time before jobs and investment started pouring in.

There is little indication of a change in direction a year into his second term. The majority of manufacturers are taking a hit as a result of the new protections, paying higher taxes on their imported components and wondering whether tariffs will last long enough for restructured supply chains to pay off.

Some manufacturers are benefiting from the new protections. The factory industry as a whole is neither thriving nor failing. Employment has fallen by 68,000 jobs over the past year and remains at just 8 percent of the work force, but production is slightly up. In surveys, manufacturers remain pessimistic. Spending on factory construction has fallen from the end of the Biden administration, but it’s still near record highs.

The mixed picture backs up the view of some economists that tariffs can help protect certain industries, but often come at a high cost. Bradley Saunders, a North American economist for Capital Economics, stated, “It creates this patchwork effect.” “A lot of unintended consequences are created by it.” People like Drew Greenblatt, owner of Marlin Steel Wire Products, a Baltimore-based company that makes metal racks and baskets for food processors and aerospace companies, are among the beneficiaries. After being hammered by cheaper Chinese imports, Mr. Greenblatt became a cheerleader for tariffs.

He now believes that they are paying off. He recently purchased the most expensive piece of company equipment ever: a TruMatic 3000 punch laser machine that will accelerate production. “You don’t buy expensive things if you’re not going to hire a lot of talent. That can be seen in our own small way, Mr. Greenblatt, who says he plans to hire at least 20 more people in the coming year, employs 130 people. “I’m going to be buying 10 times more steel, so my steel company is going to be sending me valentines early.”

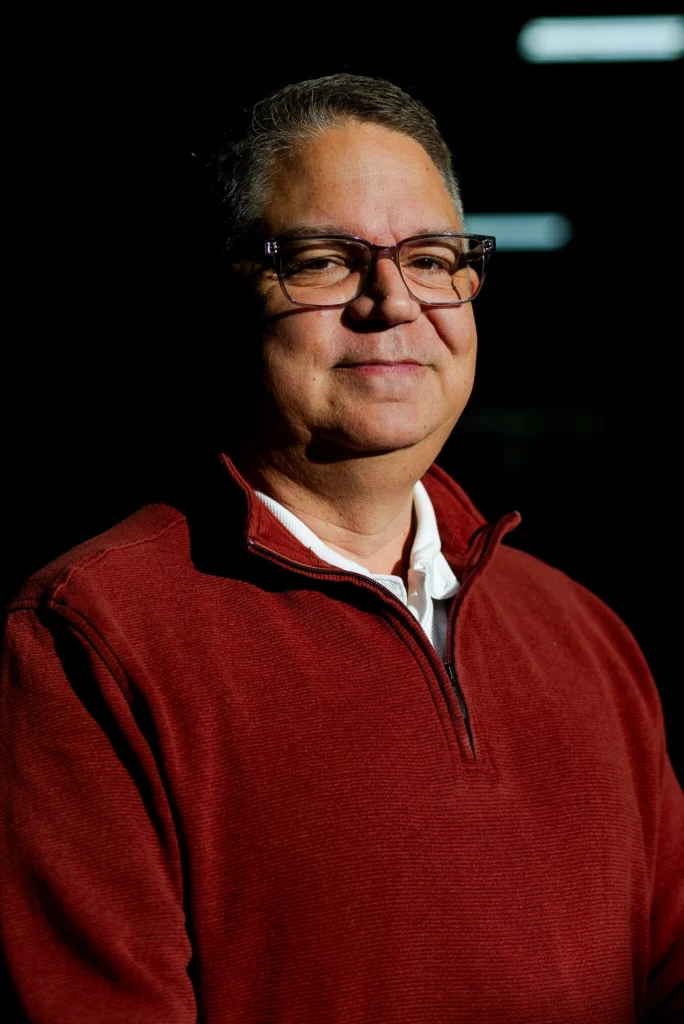

But many manufacturers see only downsides from tariffs. Lou DeCuzzi’s company, DRR USA, makes electric and gas-powered all-terrain vehicles in Brunswick, Ohio. He buys most of his batteries and other parts from Taiwan, South Korea and Vietnam because they’re not available domestically. With the help of Cleveland State University, he developed a plan last year to export to overseas hotels and resorts building fleets of eco-friendly touring vehicles.

“We start out the year gangbusters, absolutely on fire,” Mr. DeCuzzi stated He planned to add a second building and hire more people, before the tariffs hit and threw his pricing models into disarray. Another obstacle was created by other nations imposing retaliatory tariffs. “You don’t know what’s going to happen from day to day once this tariff war started,” Mr. DeCuzzi said. “It just crushed it, just completely eliminated sales outside the U.S. for the last six months.”

Now the plans for a new building are off, and he’s hoping domestic customers fill the gap.

There were some high points, but there were also many low points. Over the past decade, the idea that globalization was not an unalloyed good for the United States has gained traction on both the political left and the right. Tariffs were welcomed by policymakers as a means of safeguarding strategically important industries. President Joseph R. Biden Jr. maintained many of the tariffs that Mr. Trump had imposed in his first term, and supplemented them with subsidies to support sectors like semiconductors and batteries.

Mr. Trump’s approach in his second term has been radically different. New tariffs have been imposed on nearly every nation and a wide range of goods, including those that the United States hasn’t made in a long time, in addition to a desire to increase revenue. Some of the heaviest duties are being collected on inputs, like steel or machinery, that other manufacturers need to make their goods. Anyone thinking of starting a factory in the United States often has to factor in those higher costs.

Jamieson Greer, Mr. In an interview this month, Trump’s top trade negotiator acknowledged that it was difficult to impose tariffs that wouldn’t hurt some companies that import parts and materials. But he said the problem underscored that some companies were “dangerously dependent” on foreign supply chains.

“There’s going to be frictions like this,” he said. “And I think that we are trying to look at it from a long-term perspective.”

Still, there’s not much to suggest a boom is underway. Juan Arias is the director of industrial analytics for CoStar, a real estate data firm, where he can see how many people are searching for factory space on the company’s listing website. Activity was heating up until last April, when Mr. Trump announced tariffs across nearly every country. Search activity then fell sharply.

“The feeling in the industry was rising, and all of a sudden, I can’t expand as a manufacturing player in your country because I don’t know how much I’m going to pay for the inputs,” Mr. Arias said.

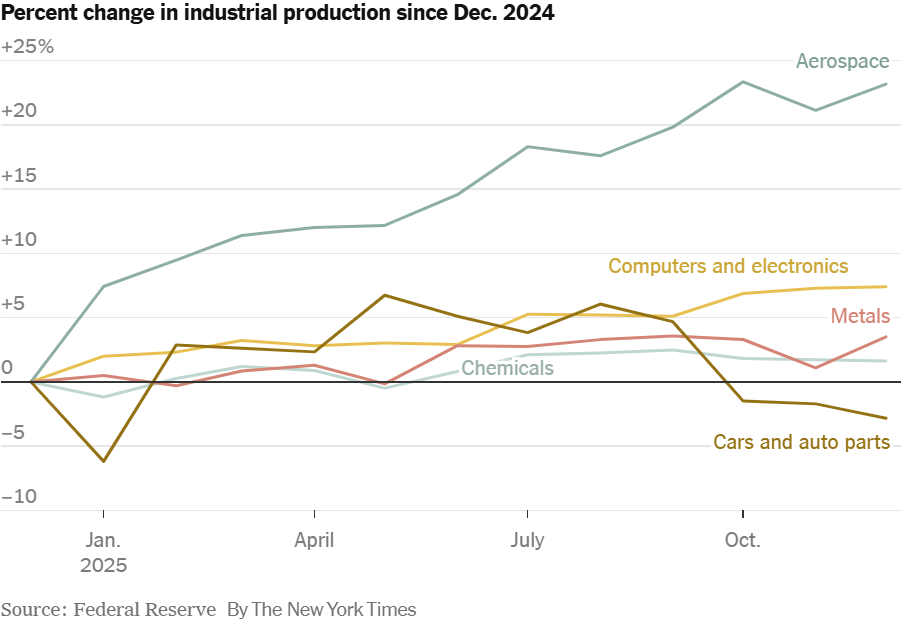

Manufacturing Isn’t a Single Process Makers of products exempt from tariffs, like electronics and airplanes, have fared better than some with heavy tariff exposure, like automobiles.

Better fortunes have been enjoyed by the companies that manufacture those raw materials, primarily iron and steel. Mr. Trump reimposed a 25 percent tariff on foreign steel in February and raised it to 50 percent in June.

Prices for both imported and domestic primary metals have increased slightly over the past year. Cleveland-based steel manufacturer Cleveland-Cliffs CEO Lourenco Goncalves called the tariffs on his industry “absolutely necessary and overdue.” He has sold more steel to U.S. automakers over the past year, though he said they were bringing business back to the United States “much more slowly than I would like to see.”

In the long run, Mr. Goncalves sees only one way to comply with what the Trump administration wants manufacturers to do. “Bring production back to the United States and then there are no more tariffs, life is good,” he said.

From the automakers’ perspective, it’s not that easy. Cars and car parts have been some of the most heavily taxed products, and production has slumped in recent months.

Jeff Aznavorian is the president of Clips & Clamps Industries, which manufactures a wide array of fasteners that go into cars made in the United States. He has paid more for steel and copper and raised his own prices in response. He received a plethora of inquiries from automakers and their suppliers seeking to relocate imported parts, but none of those quotes resulted in orders because the move was still prohibitively expensive.

At the same time, the automakers have not been introducing new products because they are nervous about the future of the U.S.-Mexico-Canada Agreement, which has allowed for the continued flow of many duty-free parts. It’s up for renewal this year, and Mr. Trump has threatened to scrap it.

“We’ve spent the last 40 years building up a trade bloc to compete with the rest of the world,” Mr. Aznavorian said. Our customers are unable to make investment decisions when we do not know whether that will hold. Still, he feels lucky to be in business — some auto suppliers have gone under. Tenneco, a part owner of United Piston Ring in Manitowoc, Wisconsin, blamed “changing market conditions and an increasingly challenging economic environment” for the company’s announcement that it would close and lay off 60 employees beginning in March.

Attrition is being used to reduce headcount in other businesses. Those manufacturers, like those in the aerospace industry, that have stayed away from tariffs are doing the best. Mr. Additionally, Trump lifted tariffs on pharmaceutical companies, some of which pledged to produce additional medications in the United States. The entire industry has avoided duties, even on imported chemical ingredients. The electronics and semiconductor industries received an exemption last April after Tim Cook, Apple’s chief executive, promised to make more iPhone parts in the United States.

Chuck Robbins, the chief executive of Cisco Systems and chair of Business Roundtable, an association of executives of big companies, said that exemption had been helpful for technology companies. He stated that, generally, the impact of tariffs varied by industry. “It depends on where certain industries have supply chains, the global competitiveness of these industries and what exemptions might have been put into place,” he said.

Beyond tariffs, fiscal policy has also created both headwinds and tailwinds. New military spending and arms sales to other countries have bolstered defense and aerospace production. But removing Biden-era subsidies for clean energy has prompted a wave of cancellations of planned investments, according to Rhodium Group, crushing the emerging industry.

Additionally, businesses have praised the administration for eliminating safety and environmental regulations that they claim were costly. Another variable: Small manufacturers, which have fewer resources to pay tariffs and less leverage to pass along prices, are faring worse than bigger ones. Their overseas rivals have sometimes taken on more of the tariffs than they anticipated.

Eric Hagopian runs a 35-person factory in Massachusetts called Pilot Precision Products, which makes cutting tools. He was optimistic about gaining an edge over companies in India and China that make similar products for far less, but tariffs haven’t helped much.

“The foreign competitors have not raised their prices proportionately, and it’s created an uneven competitive environment for us,” Mr. Hagopian said. He thinks those importers must be somehow evading the duties. Sincerely, I believe they could assist us if enforced.

Uncertain Future It is possible that the factory will experience a rebound in 2026. Numerous manufacturers had hoped that this year’s lull in tariff changes would make it easier to invest. A pending Supreme Court decision on the White House’s ability to impose tariffs on national security grounds may yet deprive Mr. Trump of his most flexible trade weapon.

Manufacturers are also excited about the provisions of last year’s major tax and spending law that renews tax breaks for research and development, and new equipment. That might motivate factory owners to put money into machinery and get more use out of the factories they already have. After the pandemic, the Alliance for American Manufacturing, led by Scott Paul, said that manufacturers were also benefiting from a trend toward more secure supply chains. “This is a not a Trump boom or a Biden boom, but it is, at least recently, the new normal for American manufacturing,” Mr. Paul stated “There are a lot of things that are making that happen.” Throughout the United States, numerous factories are still being constructed.

However, the majority of it is investment in semiconductor factories that had been previously announced and received $50 billion in subsidies from the Biden administration. Interest rates remain high for those considering future investments. Additionally, as a data center boom raises electricity costs, what had been a comparative advantage for U.S. manufacturers is becoming an obstacle. The unpredictability of the upcoming policy, according to advocates and opponents of tariffs, may be the most detrimental effect of all.

As Mr. Trump’s popularity plummets as a result of persistently high prices, and the possibility that tariffs will be suddenly lifted is just as discouraging as the fact that they are currently in place. Research suggests that while well-designed, permanent tariffs could raise manufacturing employment over time, transitory ones would bring about no such payoff.

“That’s why we hear a lot about the near-term pain and hear fewer stories about short-term gains,” said Stephan Whitaker, a policy economist at the Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland. “The gains, if there are going to be any, would be over the longer term when it’s clear that some of the domestic markets are being protected.”