In the Documentary Oscar Nominees, Acts of Defiance Big and Small

Each contender demonstrates the power of nonfiction filmmaking by involving subjects and even directors who challenge authority in different ways. Documentaries tend to be about — and are sometimes made by — people who refuse to do as they’re told. However, the Oscar nominees for best documentary feature this year are brave and subversive even by those standards.

Each is a story about standing up to something that seems too big to face: an authoritarian government, an abusive system, or social norms that make people less human. Together, they show the power of nonfiction filmmaking, both amateur and professional, in those acts of resistance.

The five nominees appear to be very different from one another. The movie “Cutting Through Rocks,” which is currently playing in theaters, follows Sara Shahverdi, the first woman elected to the council of her village in a remote part of northwestern Iran, as she challenges authority. She is a divorced former midwife who lives on her own, which is almost unheard of in her community.

The film’s directors, Sara Khaki and Mohammadreza Eyni, show how she works tirelessly to uphold and guide the village’s women against patriarchal norms supported by the law. “Mr. The movie “Nobody Against Putin,” which is currently playing in theaters and is directed by David Borenstein and Pavel Talankin, is also about not liking an authoritarian government. The Russian government ordered Talankin, a teacher, to teach pro-war messages in his classroom following the Russian invasion of Ukraine. He and his colleagues were instructed to film their lessons to demonstrate this.

Talankin decides to resist by secretly making a documentary about classroom propaganda using his footage. He gets along with Borenstein, and the result is a movie that has been nominated for an Oscar. Two additional nominees also have footage shot in unconventional ways. Andrew Jarecki and Charlotte Kaufman’s HBO Max film “The Alabama Solution” was largely shot by men incarcerated in Alabama prisons over a decade, using phones smuggled in against rules.

They depict appalling living conditions, including images of brutalized bodies and blood and feces smeared across the floor, and they argue that lies and willful ignorance are enabling massive human rights violations. The film would never work if images were secretly captured. Meanwhile, Geeta Gandbhir’s Netflix film “The Perfect Neighbor” depicts the Florida murder of 35-year-old Ajike Owens in 2023 to argue against the state’s “stand your ground” laws. In the first half, the movie uses a lot of footage that can only be seen under surveillance: recordings from home security cameras and footage from body cameras used by sheriff’s deputies.

Later, the film draws from cameras located in a police station to show an interrogation.

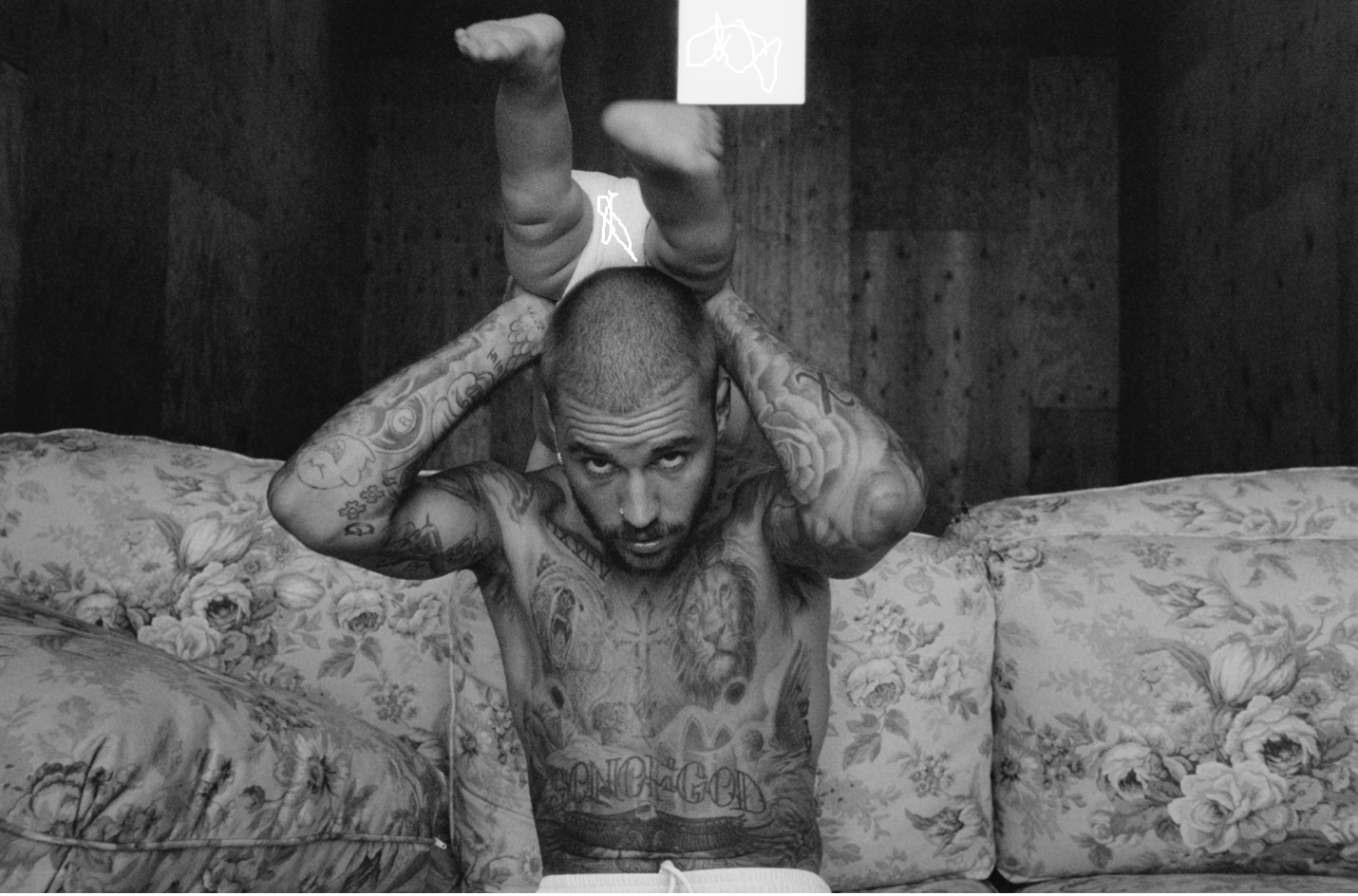

This video’s nature is altered when it is repurposed for a documentary, making it a persuasive and memorable weapon against the law. The last entry, “Come See Me in the Good Light” by Ryan White (Apple TV), is about a different kind of defiance. It is a personal account of the poet Andrea Gibson and their wife, Megan Falley, in her final year of life after she was diagnosed with terminal cancer.

The film fills in the couple’s back stories, showing some of the struggles they had to overcome to find one another — Gibson’s journey to accept their gender and sexuality, Falley’s path toward body acceptance and love.

However, the film’s utter joy in the face of certain death may be the most remarkable aspect, particularly for those who have been through a terminal diagnosis with a loved one. Gibson begins by reading one of their poems and says, “My story is about happiness being easier to find once we realize we do not have to find it forever.”

The world is full of strife and turmoil and death, all of which can make us feel scared and angry and alone. In the midst of those realities, insisting on joy and laughter might be the most insubordinate act of them all.