Brazil’s President Receives Renewed Support Due to Anti-Trump Bump

President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva of Brazil, formerly known as the world’s most well-liked politician, had little chance in the election the following year. That is shifting because of President Trump’s tariffs.

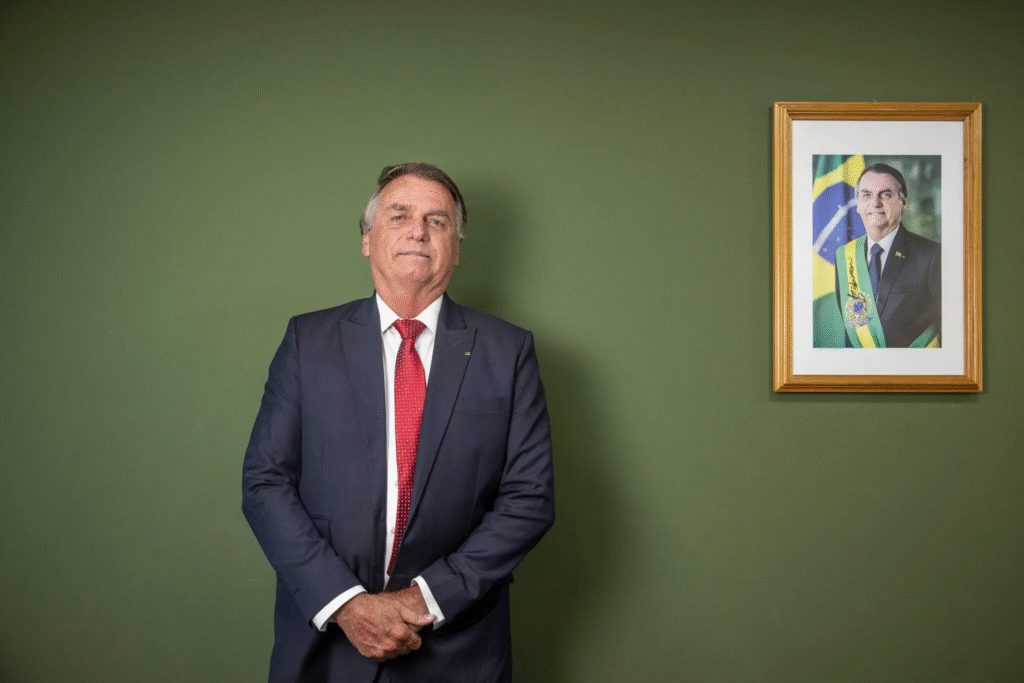

The presidential contest in Brazil next year was shaping up to be one that Americans might recognize: an older incumbent with waning popularity trailing a brazen populist who alleged that the previous election had been stolen from him.

After that, President Trump walked in.

The political scenario in Brazil has been altered by Mr. Trump’s threat last week of a 50% tariff on Brazilian exports in an effort to protect his ally, former president Jair Bolsonaro, from potential incarceration, which has given President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva an unforeseen lift.

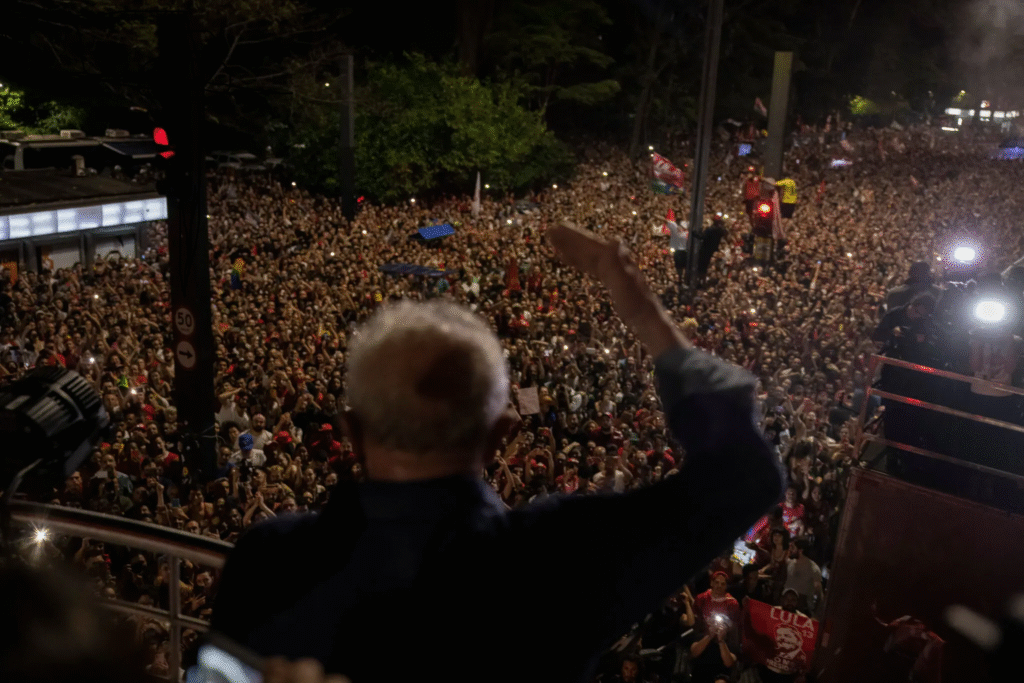

Mr. Trump’s politically driven tariffs serve as a foil for Mr. Lula’s message, which is now quite straightforward: We will not be intimidated by a bully. Days before his 80th birthday, his position is winning media acclaim, becoming popular online, and giving his followers renewed optimism that Mr. Lula may win a fourth term the following year.

Days after Mr. Trump’s tariff threats, Mr. Lula’s approval ratings hit their highest point in months, giving them cause for optimism. New polls revealed that between 43 and 50% of Brazilians supported his performance, which was a three to five percentage point increase from May.

Camila Rocha, a political scientist at the Brazilian Center for Analysis and Planning, a research center, said, “This greatly strengthens the president.” “It was a stroke of luck for the president.”

The shift in public opinion is just one manifestation of the anti-Trump bump, a worldwide trend that has transformed elections in Canada, Australia, and other nations by increasing support for candidates who challenge the U.S. president.

Mr. Lula’s popularity in Brazil fell to its lowest point during his three terms this year as a result of growing food prices and domestic policy missteps. It seemed that it was time for someone new to take over the reins: 57% of Brazilians opposed his candidacy for reelection.

In response to what he termed a “witch hunt” against Mr. Bolsonaro, who is facing criminal charges of plotting a coup following his defeat in the 2022 election, Mr. Trump then threatened Brazil with harsh tariffs last week.

Mr. Lula’s reaction to the danger was strong and immediate, indicating that he was willing to talk but would not waver in the matter of Mr. Bolsonaro. “Brazil is a sovereign nation with independent institutions and will not accept any form of tutelage,” he declared.

The new tariffs would go into effect on August 1, not long before Mr. Bolsonaro is scheduled to stand trial for allegedly masterminding a massive plot to rig the election, destroy the courts, and grant the military special powers. The scheme, according to the cops, involved preparations to kill Mr. Lula.

Although Mr. Bolsonaro claims not to have been aware of any plans for an assassination or coup, he does concede that he looked into “ways within the Constitution” to stay in power. He stated that he was “not pleased” by Mr. Trump’s tariffs but proposed that, in order to achieve an economic truce with the United States, he and his allies should be granted immunity from prosecution.

He has urged Congress to pass an amnesty legislation at the urging of his allies. Such a law would probably be vetoed by Mr. Lula, but Congress has the power to override a veto.

In response to U.S. tariffs, Mr. Lula has pledged to impose taxes on American goods. With around $92 billion in trade, the United States enjoyed a trade surplus of $7.4 billion with Brazil in 2022.

Brazil, the United States’ second-largest trading partner, might experience a devastating economic blow from a tariff war, which would increase food, medicine, and fuel prices as well as inflation.

Historically, Brazilians have attributed economic upheaval to those in positions of authority. However, by holding Mr. Bolsonaro and his son, who has been lobbying the White House on his father’s behalf, accountable for the tariffs, Mr. Lula may be able to avoid public wrath.

“The former president should assume responsibility,” Mr. Lula has said. “It was his son who went there to influence Trump.”

Despite a court prohibiting him from seeking public office until 2030 due to spreading unfounded claims about election fraud, Mr. Bolsonaro claims that he intends to run again the following year. In polls taken earlier this year, he had a narrow advantage over Mr. Lula, but the difference was inside the margin of error.

Rosana Pinheiro-Machado, a specialist on Brazil’s populist politics and a professor at University College Dublin, stated that “Bolsonaro’s core base will not change its mind” but that moderates may.

Former President Barack Obama once referred to Mr. Lula as the “most popular politician on Earth.” From 2003 to 2011, he presided over a prosperous period in Brazil that was fueled by commodities. Later, he was imprisoned in connection with a massive corruption conspiracy, but his conviction was overturned, giving him the freedom to run and barely win against Mr. Bolsonaro.

A string of home problems have hampered Mr. Lula’s ability to act. He has also had trouble pushing his agenda, running up against a Congress led by centrist and right-wing parties.

A fall in the shower last year raised concerns that Mr. Lula may need to make way for a younger replacement. .

However, according to Andrei Roman, CEO of AtlasIntel, a pollster based in São Paulo, Mr. Trump has helped draw Brazilians’ attention to topics like sovereignty and nationalism.

“It gave people new criteria to evaluate Lula,” he stated. “And, for now, it’s helping.”