With the same objective—conquering America—Oasis brings a 16-year hiatus to an end.

The British group is well-known in their own country, where they will perform their first reunion concert on Friday. Although they have done well in the United States, the Gallaghers are still not persuaded that they have arrived.

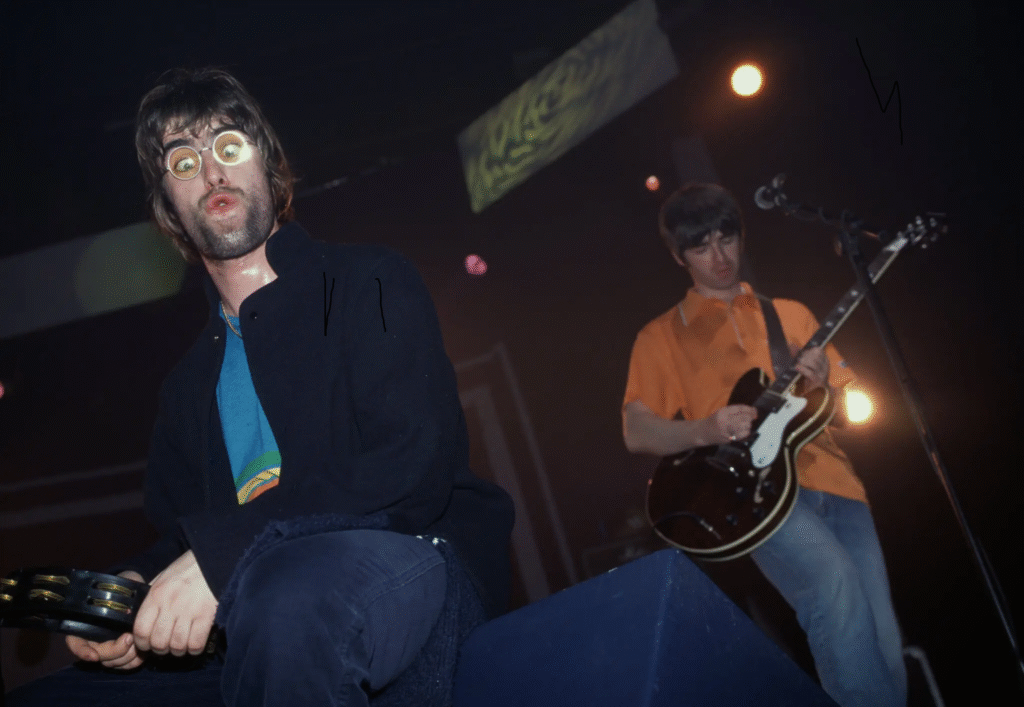

When the contentious British group, headed by the Gallagher brothers Liam and Noel, revealed last August that it would be reuniting for its first tour since 2009, it issued a statement brimming with the same kind of bombastic splendor and bravado that defined its ascent in the 1990s: “The guns have fallen silent. The wait is now over, and the stars are in alignment. Come and have a look. It won’t be broadcasted.

A few weeks later, the band announced the North American leg of the tour in a somewhat more passive-aggressive manner: “America. Oasis is coming. You have one last chance to show that you loved us all along.”

The fact that these two statements are so far apart from one another speaks volumes about the trans-Atlantic legacy of this aggressive group, which will perform the first concert tour in Cardiff, Wales on Friday. Before arriving in North America in late August for a nine-show run, Oasis will perform sixteen stadium performances throughout Ireland and the United Kingdom; after that, there will be two more shows in London, followed by dates in Asia, Australia, and South America.

Reportedly, 14 million people attempted to purchase tickets for the U.K. performances when they went on sale last August, which caused ticketing websites to fail and enraged fans. Tickets for the North American concerts also went quickly in October, selling out in an hour. “The biggest on-sale in history,” as Michael Rapino, the CEO of Live Nation, later described it.

The fact that the Gallaghers have been sniping at one another for more than ten years makes this reunion all the more intriguing. The band’s seven albums, which spanned from 1994 to 2008, were already reminiscent of classic rock when they first came out, and the music has also held up well.

“Wonderwall,” has become an inescapable anthem. With more than 2.3 billion streams, it ranks third among the most popular songs from the 1990s on Spotify. Hundreds of millions more plays have been accumulated by covers of the song in every conceivable genre, including rap-rock, country-soul, punk-pop, chillwave, metalcore, big band, lounge-pop, electro-funk, cool jazz, bossa nova, dubstep, and mariachi. The melancholy songs “Don’t Look Back in Anger” and “Champagne Supernova” have gained nearly as much popularity and have demonstrated comparable resilience to a wide variety of interpretations.

“Nobody is writing that kind of material these days,” said Maggie Mouzakitis, the band’s tour manager for the majority of its existence. “Not even themselves.”

The music established a fan base that spans generations and national boundaries, removed from the cultural context of the band’s initial rise to fame and the tension between its leading members.

“Time is the ultimate arbiter, and their music has prevailed,” said Stu Bergen, who was employed at the band’s American record company. “People who don’t know Oasis know their songs.” Bergen intends to bring his own children, who are in their twenties, to the reunion performances. “There aren’t many bands I’d want to see that my kids would be that excited to see too.”

Oasis has been highly successful in the United States by many standards. The band has sold over seven million albums in this country, had a top 10 hit with “Wonderwall” in 1996, hit number two on the Billboard 200 with its 1997 album “Be Here Now,” and played many sold-out shows at Madison Square Garden. However, even among its own members, Oasis has never fully disproved the notion that it failed to win over America.

Noel, the group’s guitarist and songwriter, told CNN in 2012 that “we nearly got there.” “However, I have no idea what cracking America is meant to be. We did it if it’s selling out arenas everywhere with a nightly audience of 10,000.

The perception is, in part, a question of comparison. The Gallaghers’ tumultuous rivalry and decadent behaviors, along with an abundance of tunes that deliver enduring classic-rock riffs with swaggering punk-rock attitude, catapulted Oasis to overnight fame in the United Kingdom.

“Definitely Maybe,” its debut album, broke the record for the fastest-selling debut in British history. The second, “(What’s the Story) Morning Glory,” is the best-selling album of the 1990s in the United States. At what were then the biggest outdoor shows in the nation, Oasis performed in 1996. During this time, Tony Blair’s political standing was supported by Noel’s public endorsement, which also helped make Oasis a key figure in the mid-1990s Cool Britannia movement.

Oasis continues to be a generational icon in England, on par with David Beckham, the Beatles, and Harry Potter. It was just a well-liked rock group in the United States.

When Oasis first arrived to the United States in 1994, the environment was not favorable for a melodic British band, according to Bergen, who rose through the ranks to become vice president of promotion at Epic in the 1990s. “Grunge was dominant,” Bergen stated. “Since the Police, no British rock group had achieved mainstream success in the United States.” ‘Definitely Maybe’ brought us more success than any other British rock group had in the previous decade. That laid the groundwork for a successful run.

Nevertheless, the band’s collective shoulder still carries an America-shaped chip. In a book compiling interviews for the documentary “Supersonic,” Liam, the band’s vocalist, stated, “I wasn’t bothered whether we made it in the States. We’d give it a good crack, but it would have to be on our terms.”

Noel was at a table with “a table full of Jack Daniels and other stuff” when Abbot arrived, he said. He felt that the band was done for.

According to Abbot, the two took a “three-day bender” to Las Vegas. Noel was ultimately persuaded by Abbot to rejoin his Texas buddies in order to record some B-sides, such as “Talk Tonight,” a song he had just penned about his break from San Francisco, despite the cancellation of two weeks’ worth of performances. For a short period, the crisis was avoided, but there had been a fundamental change.

“From then on, it was the Noel Gallagher show,” Abbot stated. “The way the band was run became nonnegotiable.”

Oasis wasn’t a smooth running operation because of Noel’s leadership. Two months into the tour supporting “(What’s the Story) Morning Glory” in 1995, its bassist Paul McGuigan left the group, claiming to be mentally exhausted. Scott McLeod, his emergency replacement, resigned after just one week. Because Liam’s voice gave out, additional tour dates were frequently cancelled during the course of the group’s existence.

“It was always the same reason: Everyone’s partying,” said Iain Robertson, who wrote the book “Oasis: What’s the Story?” about his experience providing security and assisting in tour management for Oasis during this period. “You wrap your instrument up, put it in a box if you’re a guitarist. Late-night performances took their toll, and you are the instrument since you are the singer. Because of all the partying, it was a tough trek, but we had a great time.

Courting American fans may be difficult for a British band in the 1990s. The U.S. featured dozens of markets, each with radio stations to tour, interviews to conduct, and promotional activities to attend.

“Radio and record store things always went well, but after the show, there was much less desire from the band to do that grip-and-grin stuff,” Robertson remarked. “Very often, those things went south because the band, to their credit, were never really interested in playing the game.”

As Oasis’s reputation in its own country improved, so did its tolerance for the mechanics of the American music business. The group walked out after only one hour of a cover shoot for Rolling Stone, which had scheduled eight hours for it. The band was forced to wait backstage for hours prior to playing “Champagne Supernova” at the 1996 MTV Video Music Awards. Liam, who was furious, slammed down the microphone and teased the crowd, changing a chorus to “Champagne Supernova up your bum.”

This sort of action, though perhaps annoying to promoters and management, was a crucial component of Oasis’ appeal. “People latched onto that punk-rock attitude,” said Mouzakitis. “Music was a little safe at the time. Although having to cope with the destruction of this or that was horrible, a part of me chuckled since at least they were doing something contentious.

However, Oasis may be its own worst foe. Liam made the last-minute choice to forego the band’s flight to Chicago and go house hunting with his then-fiancée, actress Patsy Kensit, as he began a 1996 U.S. tour.

Noel remembered in 2011 to The New York Times Magazine, “The first gig was a 16,000-seat arena, and the singer’s not turned up.

Liam’s absence from that Chicago show didn’t exactly derail Oasis’s progress, but it didn’t help either. The tour came to a stop abruptly when the brothers got into a fight.

“Either never begun or never completed four American tours in a row,” Noel stated in 2012. “We treated the American attitude with scorn since they are a very professional business society, which caused us to get off to a bad start with them.”

Growing up in Burnage, a rough neighborhood in Manchester, the Gallaghers occasionally found it difficult to connect with American viewers. “Our accents caused us to be subtitled on American TV,” Noel continued. “People couldn’t comprehend a word we were saying, basically.”

The disparities between the United States and the United Kingdom were more obvious in the pre-internet 1990s, and Oasis was a member of an urban British working-class cultural milieu that had no actual American counterpart. “The whole ’90s, post-rave, Brit lad culture, which was, like, music, football, Adidas cagoules, cut your hair a certain way, it was a thing,” Mouzakitis said. British children of a generation saw themselves in Oasis. “That sort of feeling didn’t translate in America.”

The Gallaghers made several changes to the band’s lineup, but it was the tension in their relationship that drove both Oasis’s creative force and its downfall. In the most Oasis way possible, everything fell apart in 2009. Liam and Noel got into an argument just before they were scheduled to perform as the main act at a Paris festival, during which fruit was thrown and Noel left the band. He said in a statement that he couldn’t continue working with Liam for another day.

Despite the fact that both brothers continued to tour and publish albums independently, none of their solo work had the same impact as their collaborative efforts. Nevertheless, a reunion appeared improbable due to the constant stream of insults directed at one another via the media and social media. The public interest on both sides of the Atlantic was undeniable after the news broke last summer.

Since Oasis’ last performance, the live music scene has undergone a significant transformation. More people and more revenue are generated by big trips. Between 1996 and 2009, Oasis’s average gross per concert was $252,239, according to Pollstar, which covers the concert business. In contrast, Coldplay made an average of $7.8 million in 2024.

“The turning point was right when Oasis ceased touring,” said Andy Gensler, editor-in-chief of Pollstar. “Everything became more global. This is golden age. So, their timing is exquisite.”

The Gallaghers and the other band members who have been confirmed for the forthcoming performances—the guitarists Gem Archer and Paul Arthurs (who goes by Bonehead), the bassist Andy Bell, and the new drummer Joey Waronker—have not yet made any public statements about the reasons behind the reconciliation. It was hypothesized by some of the individuals interviewed for this piece that Noel was more receptive due to his recent, expensive divorce, which British media said was pricey. Others hypothesized that it’s a present for the Gallaghers’ elderly mother, who has been upset by her sons’ discord. Everyone involved may be more able to assess the merits of the project as they get older.

“There’s a lot of venom in bands,” Gensler remarked. “However, the live industry is so lucrative that performers have every reason to ignore their differences.”

Noel and Liam must, of course, put up with each other for the duration of the tour in order for all this filthy lucre to be based on it. Their long-time tour manager, Mouzakitis, is cautiously upbeat.